- Home

- Siobhan Burke

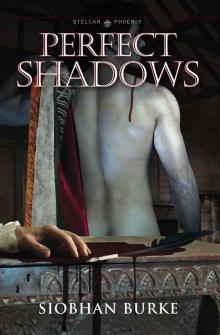

Perfect Shadows

Perfect Shadows Read online

Perfect Shadows

Siobhan Burke

Stellar Phoenix Books

Philadelphia, USA

Toronto, Canada

Copyright ©2011 Siobhan Burke. All rights reserved. No part of this work may be reproduced in part or whole, in any form or by any means, without permission from the publisher. This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously.

Stellar Phoenix Books

Philadelphia, Toronto

Printed and bound by CreateSpace in the USA

Front cover design by Jonathan Cresswell-Jones

“What are kings, when regiment is gone,

But perfect shadows in a sunshine day?”

—Christopher Marlowe

In Memory

Siobhan Burke

1950 — 2011

It is with joy as well as sadness that I sit here writing this introduction to Perfect Shadows. Joy because the novel that Siobhan labored over with so much care has finally been published and sadness that such a talent was cut short with so many projects left unfinished.

She was a life-long student of English history, and a member of the Richard III society. She thoroughly researched the period, and the historical persons portrayed in this novel, though she made no attempt to have the characters converse in purely Elizabethan English, or, in the words of Josephine Tey, have the characters speak too forsoothly, as she felt that, for all but a small number of modern readers, that distracts rather than attracts. She has, however, endeavored to avoid anachronistic modern slang, as she felt that just as distracting.

Although this was her first novel, she has had short stories published including two in Dreams of Decadence, one of which involved the main character of this novel some two hundred years after the events therein and was reprinted by ROC in The Best of Dreams of Decadence edited by Angela Kessler. Another story, A Bad Day in Sherwood was awarded first place in a national competition. She was working on, and had half completed, a sequel to Perfect Shadows, as well as outlines for a number of other novels concerning the major characters.

Her characters took on a life of their own and like wayward children, they sometimes went off in directions that surprised her. She had to cajole them into behaving when she wasn’t acquiescing to their demands. Oftentimes she followed their lead with amazing results.

I do hope that you, the reader, enjoy the completed work as much as Siobhan did writing it.

I want to thank her publisher, Jonathan Cresswell-Jones, without whose help this book might be forever languishing as a manuscript in some forgotten slush pile.

Michael Burke

South Portland, Maine — March 2012

Table of Contents

Shadows In The Sun

Or An Undead Man In Deptford

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Shadows Relict

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Shadows of Treason

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

Chapter 37

Chapter 38

Chapter 39

Chapter 40

PART ONE:

SHADOWS IN THE SUN

OR AN UNDEAD MAN IN DEPTFORD

Chapter 1

“Kit! You, Kit! Come here, I want you!” Tommy, Sir Thomas Walsingham, called as I crossed the great hall in search of coals for my brazier; my ink had frozen again. He motioned me to follow him, and I trailed him to his office. To my dismay Ingram Frizer stood leaning over his shoulder, pointing out something on the papers spread on the table before them. Tommy looked up as I entered, and motioned me to join them.

“I have work for you!” Tom exclaimed, waving a handful of paper at me.

“A commission?” I asked eagerly. “I am well begun on Hero and Leander. In fact I was working on it just now, remembering how we swam in the moat last summer....” I faltered, stopped more by the smirk on Frizer’s face than by the annoyance on Tom’s. Tom was more than half drunk, I observed, though it lacked an hour to noon. Frizer drifted over to settle upon the chest under the casement window as Tommy started to gabble at me.

“No, no, nothing so slow or uncertain as that. What we thought was this.” His voice dropped to just above a whisper as the words tumbled out faster and faster.

“Slowly, Tommy,” I said gently. “I cannot make out more than a word in three. You’ve found another way to reline our purses, I take it?” He took a deep breath, and began again.

“Cony-catching! Ingram has found a pretty poult, just begging for the p-p-plucking!” The last word seemed to amuse him, and he repeated it several times, giggling. Another deep breath ended in a hiccup, but he went on regardless. “A young country squire, come to town for the first time. Pretty and innocent, just the sort you like,” he continued, leering at me. “You’ve the easy part, just seduce him, and let Ingram here walk in and catch you—we’ll handle the rest!” I glanced at Frizer, tittering behind his hand in the window seat.

“Find somebody else,” I said curtly, and turned to go. I wanted nothing to do with extortion; I had been the past recipient of just such attention too often to desire to practice it upon others.

“No, it must be you! He’s stage struck, cannot wait to meet the mighty Marlowe!” I returned to the table and he giggled again, pouring another cup of wine. “You’ll like him, big blue eyes and long blonde hair,” he paused to stroke his own locks, still as thick and golden as the day we’d met. “A perfect Ganymede, more money than Croesus, and he’ll pay, aye, he’ll pay!” Anger welled in me, hotter with every word he spoke.

“No!” I shouted, pounding my fist on the table, knocking over the inkwell and the wine cup. Frizer growled and lunged to snatch up the papers, shaking the inky wine off of them and glowering at me. I ignored him, leaning over the table to catch Tommy by the shoulders. I had meant to shake him, but found myself drawing him closer, and saying softly, “Send Frizer away, Tommy! You don’t need him—things were so much better, when it was just we two.” I tilted my head to kiss him, but recoiled from his breath, sour with wine. He knocked my hands from his shoulders, just as other hands fell heavily upon mine. Frizer jerked me back, and my knee caught the edge of the table, knocking

it over, dumping its contents all over Tom. He screamed, brushing at the wine and ink soaking his velvets, spreading the stain, making it worse. I started to apologize, but he interrupted.

“Look what you’ve done! Look what you’ve done! Send Ingram away? Send him away? I need him. I need him far more than I need you!” Frizer’s grip tightened and he dragged me towards the door. I shoved an elbow hard into his belly, and twisted out of his grip. He was a few inches taller than I, and far heavier in build, but I was the veteran of innumerable tavern tourneys. A hard jab to the stomach, and an elbow to the back of his neck when he doubled overtook the starch right out of him.

“You cannot mean that, Tommy,” I said. He was staring in horror at Frizer measuring his length on the floor. When I started towards him, he backed away, calling loudly for his serving men. “I won’t hurt you, Tommy, you know that,” I began soothingly, when the door burst open to admit several large footmen. One helped Frizer to his feet, while two more flanked me, each taking an arm.

“You call yourself a gentleman, a scholar! You’re nothing without patronage, nothing without me! I’ve done everything for you, and you refuse me even one small favor in return! Jumped up little cobbler’s son!” Tom screamed, his face purpling with rage. I jerked free of the serving men, turned on my heel, and headed for the door.

“I did not give you leave to go!” Tom bellowed. I ignored him.

“Let him go,” Frizer growled. “He’s naught but a poet and a filthy playwright. Let him go!”

“Marlowe! Oy, Tamburlaine, over here!” It was Nashe’s voice. Peering into the tavern’s smoky gloom, I spotted his manic, gap-toothed grin behind a wildly waving tankard, and crossed the crowded room to join him. “I thought you were at Scadbury for the week.”

“I decided not to stay,” I said briefly, shedding my threadbare cloak and shaking the sleet from it. Patrons at the surrounding tables cursed or laughed as the icy spray caught or missed them, but none seemed inclined to fight, alas.

“Frizer, eh?” returned the quick-witted Nashe. “I tell you what, Kit, lets us catch him out some night, strip him mother-naked, then bind him fast to Paul’s Cross for the watch to find!” His insolence restored my humor, and I grinned, agreeing that the knave, with his pious parson’s face and pimp’s soul, deserved nothing less. “Well, never mind,” he said consolingly. “I got paid today—help me celebrate!”

We had spent an hour or so indulging in scathing observations upon our mutual acquaintances and squandering his shillings, when I spotted a new face just entering. Two new faces, a beautiful young man, and a somewhat stout, but still vigorous, older man. They exchanged a few quiet words, and the younger man’s eyes swept the common-room and stopped at me. I straightened incredulously and returned the gaze, resisting the urge to look behind me.

My preference in lovers was well enough known, but few had ever sought me out and never before a jewel such as this. The young man was gentry, from the look of the rich crimson velvet that clothed him. Wildly, I wondered if this was Tom’s cony, but no, he’d said that lad was fair and this youth was olive-skinned, with smoky, restive eyes and inky hair. He and his companion nodded to each other and he headed straight towards me. My satisfaction was a little soured by suspicion as he slid into a seat next tome, so close that our thighs pressed together. It was getting damnably hot in the room, for all it was January, and the sudden pressure in my groin was promising to become painful. I gulped at my wine and edged away from the lad, who let me go and then laughed, a throaty chuckle that set my head spinning.

“Is it fear, or desire, that so disturbs you?” he whispered, sliding a narrow hand onto my knee. His voice, husky and low, seemed almost to purr, and was graced with a faint foreign accent. I glanced around but his companion had vanished. Nashe gave me a wry and only slightly disapproving grimace and took himself off to a dice game in the far corner.

“Have I reason to fear you?” I asked, as sweat tickled my body.

He brushed my question aside with a laugh and leaned closer. “Desire, then. ‘He is a fool who loves not tobacco and boys.’, so you’ve said oft enough, or so it is told me. Do you desire me?” I nodded, unable to speak past the sudden lump in my throat. “Then meet me tomorrow evening for the Lord Mayor’s Twelfth Night masque at Crosby Place. You know where that is?” His careful manner of speech, and the odd lilt of his accent had beguiled me, but that drew me up short.

“I cannot go there!” I knew full well the sort of reception I, or any of my ilk would receive at the hands of the Lord Mayor’s grooms, but my companion brushed my objections aside.

“Then I do dare you come; have I not said it is a masque? Disguise yourself! If you have the valor there to meet me, then you have won me, but if you are a craven, then I would as lief you stay away.” He considered for a moment and then gave me a wicked, fetching smile.” Fail me not, my Leander, and look not to drown your fires in some unforeseen Hellespont of orthodoxy and security.” And I found myself alone with nothing to prove that the whole encounter had not been imagined, save for the warm place where his hand had rested on my thigh, and the hoots of my companions upon my apparent failure to gain the youth’s company for the evening. Shortly thereafter I returned to my lodgings to work out a guise for the following night, and to wonder if it were by chance or intent that the boy had referred so exactly to the mythic theme of my current work.

The following night, soberly arrayed as Machiavel, I wandered through the hall, looking for the lad. There were rivers of strong wine and wassail bowls liberally laced with brandywine readily available. I drank deeply, and as my stomach had been all but empty, I was soon far from sober.

I almost failed to recognize my quarry when I found him—or rather, when he found me. He was dressed as Hero, and not just any Hero, but my very creation, from my unfinished poem Hero and Leander. I was stunned by the advent of my imagined heroine in the all-too-physical flesh. The lad had copied the description of the robe exactly, the impertinent whelp, right down to the Venus with Adonis at her feet embroidered on the sleeves—only the veil was missing. His long dark hair, worn loose over his shoulders in glittering auric waves and I was fascinated to see that it had been pomaded and liberally powdered with gold-dust.

Hero made a deep curtsy. “Will you dance with me, my lord?” The neck of the robe gaped for a moment and I had a clear view of the small breasts it concealed. With a shocking shift of reality, I realized that my beautiful boy of the night before was indeed a woman. I was repelled, yet also unaccountably attracted. Yes, very attracted.

“Lady, I cannot,” I answered in a shaken voice. No woman had ever had such an effect on me before and damned few men.

“Then we shall speak together,” she said, tucking her arm through mine. My head was whirling. I thought of Tom, whom I had loved, and of the bitter quarrel that had parted us. He was making a great show of indifference, which hurt me as badly as any of the cutting things he’d said, worse even than his throwing my humble birth up in my face. We crossed through a room of tables setup for the gamblers, many of whom I knew, from their patronage of the playhouses. One of them started to stand as we entered. Ingram Frizer. Good, I thought, then Tommy was bound to hear of this and be sorry, or better still, as hurt and angry as I. My companion gave me no time to stop, however, but drew me into a private parlor beyond, and Frizer dropped back into his seat, muttering to his tablemates. There was an outbreak of bawdy laughter as the door was pulled shut and bolted behind us.

There were many pillows spread before the fire and a tray with drink and sweetmeats. She pulled me down beside her and poured wine red as blood into fragile cups of Venetian glass. My hands were shaking as I took the cup she handed me and garnet drops stained the ragged white frill at my wrist.

“Speak to me,” she said, “about yourself. Oh, not those things that anyone might know,” she added, with a low laugh. “Tell me what lies hidden here,” and she laid a cool hand upon my heart. I was repulsed by her forwardness but, ev

en against my will, still more attracted and we conversed for a time. Her soft questions drew the answers from me as if my mouth had become a wound she had opened, bleeding my memories away, and no way to stanch the flow.

I described to her my childhood years, spent in the shadow of Canterbury’s great cathedral, of the games the churchmen, both religious and secular, played with the choirboys, but held back my own time spent as an alderman’s catamite. I told her of attending the King’s school, that had led to Cambridge, Cambridge led to London, and London had given me success, and Tom. I trailed off, thinking of him, of the wounding words he had flung at me like so many darts, of the void in my life where I had grown used to seeing him. My companion seemed to sense my distress, and asked me about him.

“We quarreled,” I said, shortly, but she pressed me for the details, and I surprised myself by telling her all.

“I even gave up my family for him,” I continued. “Last fall in Canterbury, a disagreement with a local tailor had come to blows, and he’d screamed out his accusation on the public street: Sodomite! My father was constable, and put an end to the quarrel, but that evening he taxed me with the accusation. ‘Is what Corking said the truth?’ I wanted to deny it, at least to him, but denying that meant denying Tom, and that I could not do.” I ran my thumb over the T-shaped scar on my right hand. “So I confessed. I hope never to pass another such night as that! My mother crying, my father pacing, striking me blows now and again, which I made no effort to block. Was it something that they did? No, it was the way that I was. Who had made me so? Manwood, who had gotten me my scholarship? No! Who then? God, or no one! That earned mea blow that sent me sprawling off my stool to strike my head against one of my father’s iron lasts. They made no effort to help me, left me there bleeding from a cut above my right eye—see the scar? I knew then that they were lost to me. When I found the strength I made my way to the door, ‘I think it best that you not come again,’ my father said, thrusting my cloak and my small bundle of belongings into my hands. I’ve not been back to Canterbury, nor will I ever return to that house. I am as the dead to them, and they to me.”

Perfect Shadows

Perfect Shadows